Social Realism, New Masses & Diego Rivera

Self-expression and anarchist individuality were the result of isolation and alienation of the artist in a developing capitalist society. Art had become a commodity like any other commodity on the market, and the artist had sold themselves as well as their picture.

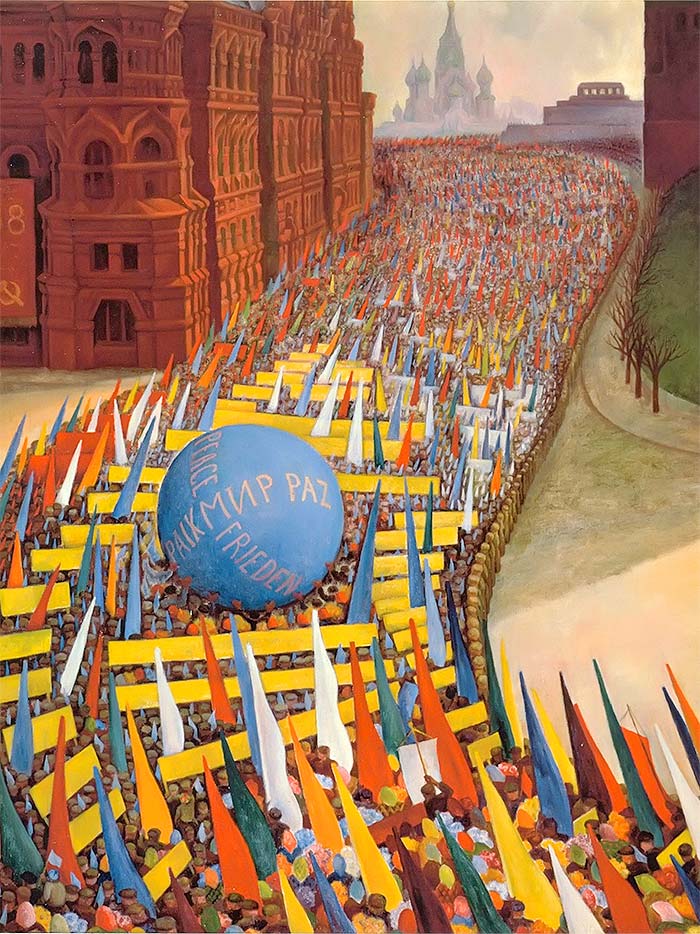

It was the 1920’s and artistic discoveries were prosperous. The extremity of fascist regimes were amplified as well as racial conflict and the intensification of economic depression, this also initiated an optimistic reaction from the public after both the Mexican and Russian revolutions. Within the above historical context of the effects of the great depression of 1929, a very large and diverse group of artists later called the Social Realists joined together to publish magazines, organise unions and convene artists’ congresses. The social realists publicly agitated for the importance of their revolutionary work, the role of the artist within society, and radical anti-capitalistic change for the world. Social Realism established a political purpose crafting emblematic and representative images of the masses, The Masses embodied the low and working class, labor unionists and politically disenfranchised. American artists found their purpose in the belief that art was a weapon to fight the capitalist exploitation of workers and halt the expansion of international fascism.

Social Realists resonated with the laborers and workers of their society, the artist’s role was to both portray and inspire their actions. The social realist artist was not to practice the self-indulgent self expression encouraged by a decadent capitalism for its own jaded amusement instead, they were to use their freedom to interpret the aspirations of a free people. Mexican muralists, namely, José Clemente Oroszo, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros were examples of this artistic interpretation. These social realists endeavoured to employ art to protest capitalist exploitation and dramatise injustice to the working class so therefore was essentially anti-establishment.

The Social Realist artist symbolised unity within the working class, personifying themselves as critical members of society. Social Realists built on the legacies of Honore Daumier, Gustave Courbet and Francisco Goya in their politically charged and radical social critiques. While modernism is most often considered in terms of stylistic innovation, social realists believed that the political content of their work made it modern.

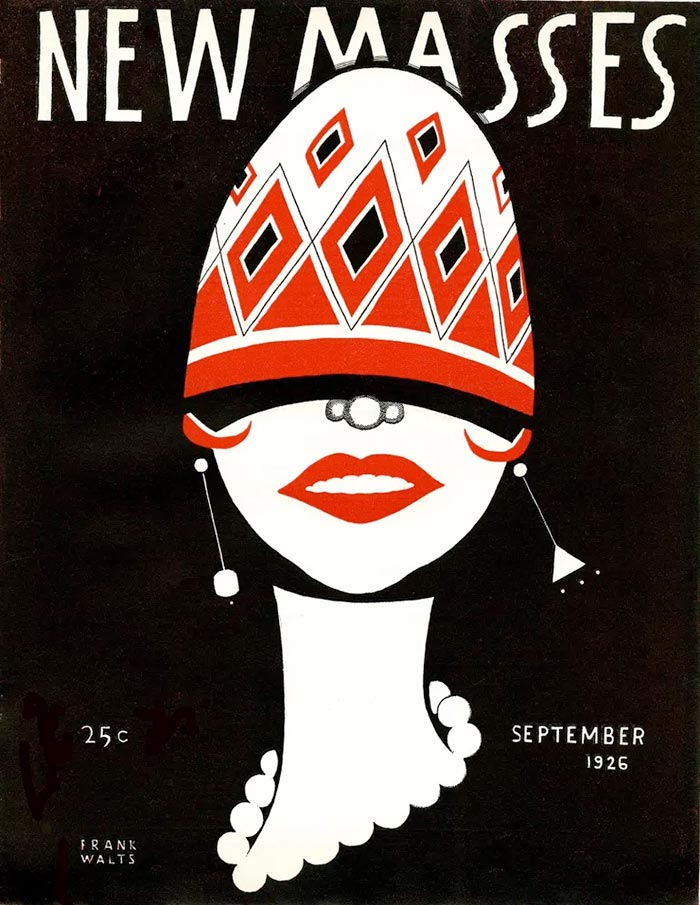

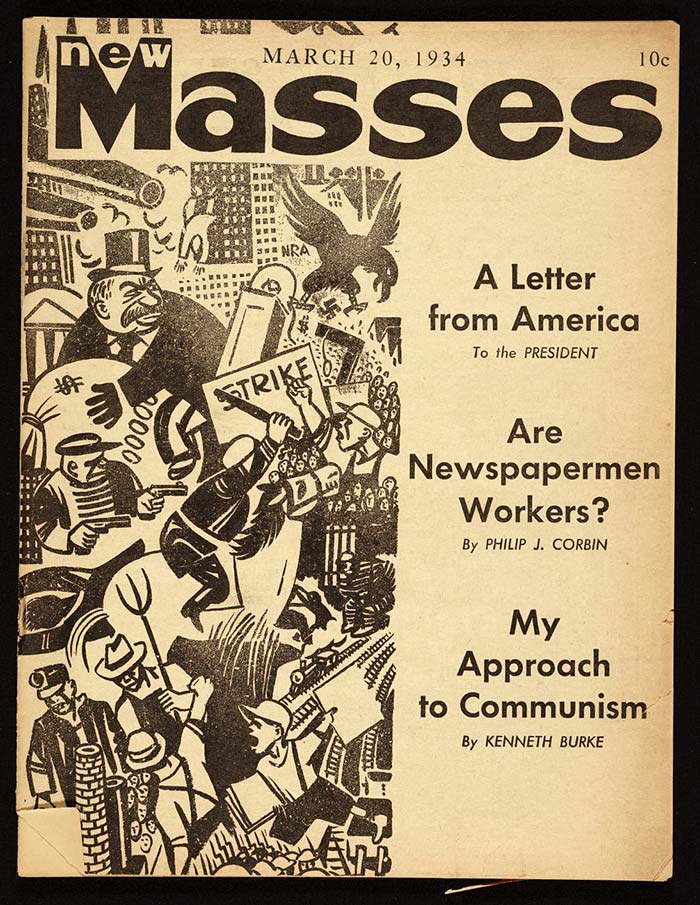

New Masses

The emergence of leftist politics inspired politically motivated social realist artists and journalists to launch New Masses (est. 1926), a progressive cultural magazine that was tied to Communist Russia. These pioneering artists also established the John Reed Club, influenced by American journalist and communist activist John Reed, the magazine itself paid homage to Reed who chronicled the Russian Revolution. Max Weber was a prominent member and was arguably a pioneer of social theory and the rapidly evolving 20th century. Weber, alongside Karl Marx and Emil Durkheim were said to have been principal founding-fathers of modern social science, contributing to the birth of new academic discipline of sociology. Weber is, to this day, claimed as a source of inspiration by empirical positivists.

Other familiar contributors of the John Reed Club were (artist and political activist) William Groper, Hugo Gellert, Moses Soyer and Raphael Soyer. The teachers of the club initially included the Mexican muralist David Alfaro, theorist Lewis Mumford, art historian Meyer Schapiro, artist Ben Shahn, and Louise Lozowick who was the main theorist of the group. The club never dictated a specific artistic style or subject matter, yet mandated that artists align themselves with the poor and dispossessed, fight for racial justice, and oppose fascism. The New Masses and its descendant the John Reed Club were radical organisations motivated by Marxist-Leninist ideology the Communist parties at that time during the late twenties and early thirties. The New Masses was closely associated with the Communist Party in the United States. America was becoming more and more receptive to ideas from the Leftist politics with the immersion of the Great Depression in 1929 and The New Masses became highly influential in intellectual circles.

A Monthly magazine was published and its purpose was to express artistic innovation.

“Sympathy and allegiance unqualifiedly with the international labour movement but were said to have no connection with any political party. A magazine of arts and letters, interpretive of American life: interested in the struggle, and in the stimulation of imaginative works created out of the new civilisation.”

Virginia Hagelstein Marquardt, The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts

Vol. 12 (Spring, 1989)

New Masses proposed its publication would welcome the expressions of all schools and regularly interpret the activities of workers, farmers, strikers and major members of the public whilst prioritising high standards of literature written by capable editors. They also endeavoured to strike its roots strongly into American reality and disclose a significant cultural and human movement, publishing stories, pictures, poems, satirical cartoons and criticisms. New Masses presented that at least half of the pages will consist of pictures of current political and social events based on the emotion of art.

Mexican revolution

A largely positive aspect of art was the art of the people, they were believed to embody everything, pure and rich. Most artists had experienced and felt the reality of labouring and living among the working masses. The Mexican Revolution had begun in 1910 emerging originally as a middle class revolt led by patrician Francisco Madero, against the degrading regime of President Porfirio Diaz. Diaz was said to establish expeditious industrialisation, submit to the control of foreign capital and, to a potentially disastrous degree form new laws designed to return the land to private ownership, essentially undoing the land reforms of previous president and favoured ideal Benito Juarez. Most of Mexico’s land was owned by wealthy landowners, 20 percent was in foreign hands, and many peasants and urban workers were living in dire poverty. The harsh reality of the revolution influenced the people of Mexico to turn to art in order to express their feelings and beliefs towards the revolt.

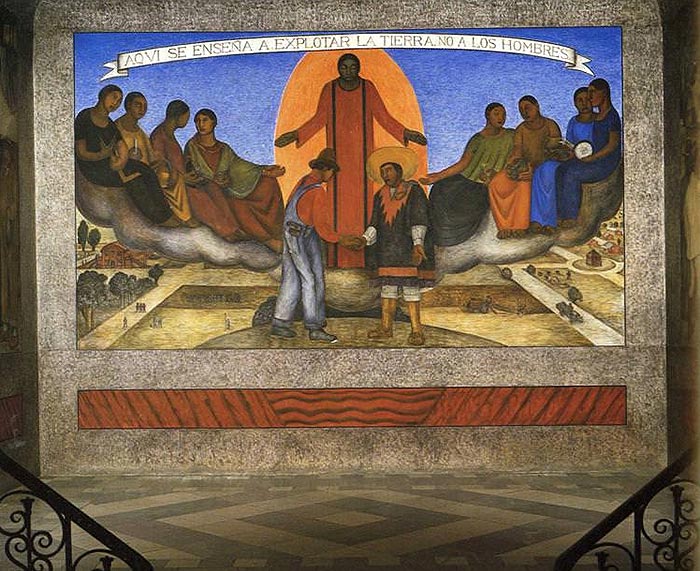

Mexican muralism was an artistic combination of artistic influences which resonated the history of the Mexican people such as Catholic conquistadors and Aztec wall painting. A movement named Los Tres Grandes prominently involving Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente and David Siqueiros was established; these influential Mexican muralists aimed to relieve and express the suppressed emotion of the Mexican people.

Rivera’s paintings and murals

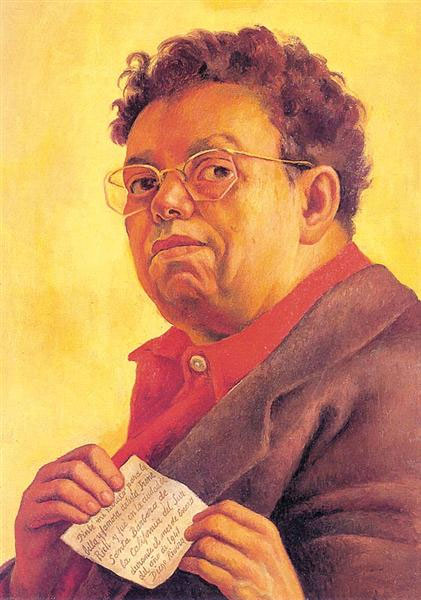

Rivera was an impressively prolific Mexican Muralist coating walls with imaginings of invention and revolt, he devoted himself to an art of complete social eloquence. Rivera held tremendous success but also faced harsh controversy, for both his political beliefs and artistic subject.

“The scope of Rivera’s art, and the national prestige it still enjoys in Mexico, came from special historical circumstances; the Mexican masses, like those of Russia, were pre-electronic, low literacy, and used to consulting popular devotional art as a prime source of moral instruction.”

Robert Hughes, Art Critic and Author of The Shock of the New

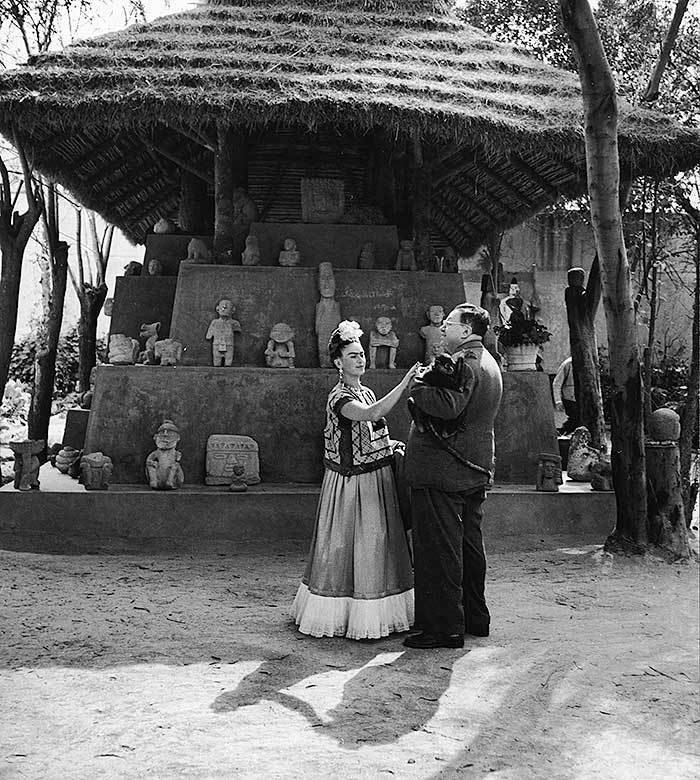

Diego Rivera was an influential and distinguished Social Realist, he is recognised for his incredible larger than life paintings, his exuberant disposition in correlation to his vigour for Communist politics and his tempestuous relationship with the renowned and honoured artist Frida Kahlo. Rivera is said to have a large zest for life and it is apparent that he was a habitual womaniser and a pure visionary, he desired to represent the social ideas of the Mexican Revolution visually and he found that the format of muralism as it existed only publicly, for the celebration, education, and edification of the ‘people’. It told the people of the masses’ story in a format that retained intense emotional resonance. His depiction of the poor, oppressed workers with great dignity and beauty resonating his sympathetic handling.

Photo: Wallace Marly/Hutton Archive (Undated) Biography.com

As a favourable and much desired artist, Rivera’s paintings embarked on a series of trips to the United States. The Mexican Communist was invited by three bastions of capitalism to create substantial murals on their behalf, this was considered highly controversial among other social realist artists and the public. The interchanging of cultural schemes, art, and the public between Mexico and America had an impact on their individual cultures. Idealistic stereotypes of one another were the result of the juxtaposition between the two countries. This however, led to their union and the sharing of one another’s ideas was said to be reconstructive. Rivera's depiction of workers united nationally and crossing borders in his murals evince how Mexicans and Americans could benefit by learning from each other.

Diana Loercher Pazicky expresses the wave of populist fervor swept over Mexico and found pictorial expression in hands of muralists such as Diego Rivera, this was a repercussion from the Mexican Revolution which chipped away at the repressive oligarchic regime and gradually brought about agrarian, educational, and labor reforms during the second decade of this century.

“Mexican muralism has not brought anything new to the universal plastic arts, nor to architecture, and even less to sculpture. But Mexican muralism — for the first time in the history of monumental painting — ceased to use gods, kings, chiefs of state, heroic generals, etc. as central heroes . . . . For the first time in the history of art, Mexican mural painting made the masses the hero of monumental art. That is to say, the man of the fields, of the factories, of the cities, and towns. When a hero appears among the people, it is clearly as part of the people and as one of them.’’

Diego Rivera

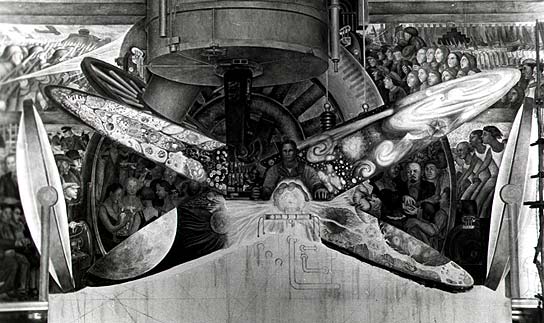

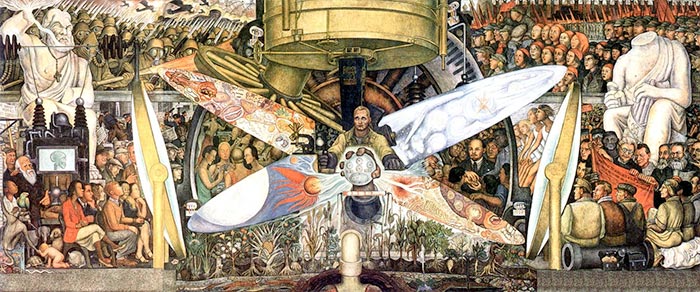

The objective of the mural “Man at the Crossroads” was initially to illustrate and portray through imagery the social, political, industrial and scientific possibilities of the 20th century. The depiction of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin leading a mayday parade disgruntled the Rockefeller’s, a prominent wealthy banking family and provoked their demand for him to remove it. Rivera refused and they then fired him, though they did pay him in full, and destroyed the mural. Rivera encourages juxtaposition between the two sides, we notice a capitalist side that encompasses the brutalities of World War I, he discloses the use of technology that the capitalist nations use as destructive forces. In contrast the right communist side reflects the splendour of the Russian Revolution, Rivera distinguishes key figures in the workers movement such as Karl Marx and Leon Trotsky.

(Khan Academy)

Rivera critiques traditional art history on the other side of the composition, placing another classical sculpture revealed as Zeus, the supreme Greek god. Rivera questions the political elite (that—in his view) —had repressed the popular masses throughout human history. Though Rivera enjoyed tremendous success, he also faced harsh controversy, for both his political beliefs and artistic practice.

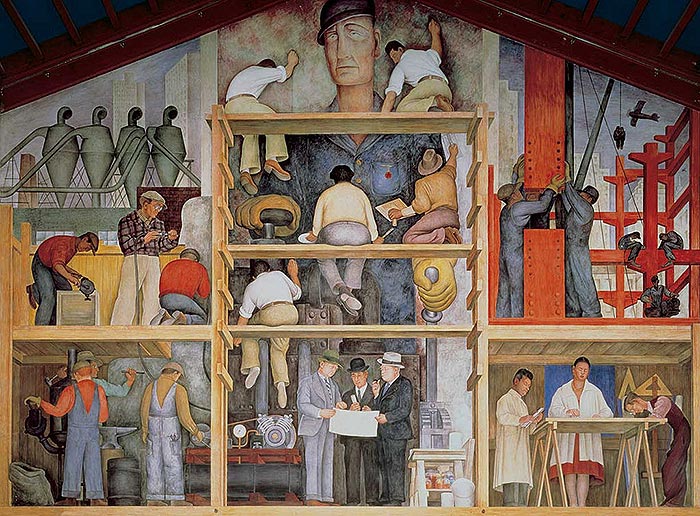

Rivera’s passion and resonance with the working man is still recognisable, in The Making of a Fresco, Showing The Building of a City (1931), he has painted himself into the history of America’s effort to build a great industrial society. There was no quit in the man, nor in his ideals and passions.

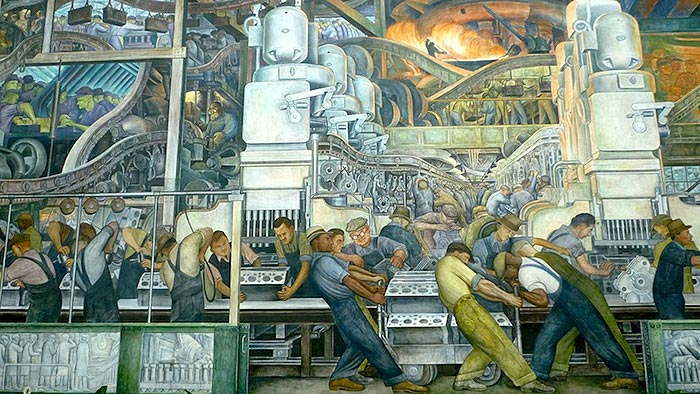

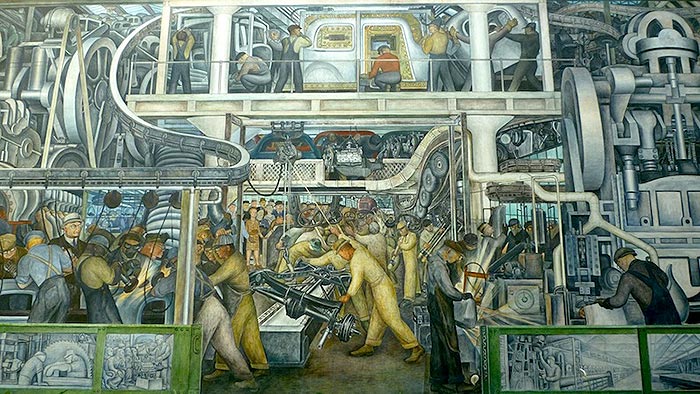

Next stop, the belly of the beast, Detroit and The Ford Motor Company. What better ode to the workers could there be than the industrial life of America at an automobile plant in the midst of the Great Depression.

Though Rivera enjoyed tremendous success, he also faced harsh controversy, for both his political beliefs and artistic practice. Though he considered his murals at the Detroit Institute of Arts (1932-33) among his greatest works, his work there faced opposition due to the depiction of men of different races working together. His politics were often disdained and his art was ironically commended, as he said:

“An artist is above all a human being, profoundly human to the core. If the artist can’t feel everything that humanity feels…until he forgets himself and sacrifices himself…if he won’t put down his magic brush and head the fight against the oppressor, then he isn’t a great artist.”

Diego Rivera

Works Cited

Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Bravo, Doris. 2018. “Diego Rivera, Man At The Crossroads”. Khan Academy. Accessed October 4.https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/art-between-wars/latin-american-modernism1/a/diego-rivera-man-at-the-crossroads.

“Essay”. 2018. Mtholyoke.Edu. Accessed October 11. http://www.mtholyoke.edu/~klcahoon/borderwebsite/essay.html.

“Diego Rivera: 1886-1957: Artist – Capitalist Art And Communist Politics”. 2018. Biography.Jrank.Org. Accessed September 21. http://biography.jrank.org/pages/3439/Rivera-Diego-1886-1957-Artist-Capitalist-Art-Communist-Politics.html.

Hughes, Robert. 1991. The Shock Of The New. 1st ed. Thames & Hudson Ltd pg. 108

Marquardt, Virginia Hagelstein. “”New Masses” and John Reed Club Artists, 1926-1936: Evolution of Ideology, Subject Matter, and Style.” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 12 (1989): 56-75. doi:10.2307/1504057.

Leeds, David. 2011. “The Passion, The Majesty, And The Politics Of Diego Rivera. | A Husk Of Meaning”. Ahuskofmeaning.Com. http://ahuskofmeaning.com/2011/11/the-passsion-the-majesty-and-the-politics-of-diego-rivera/.

“Legacy Of Posada And Influence”. 2014. The Posada Art Foundation. http://www.posada-art-foundation.com/legacy-of-posada.

(Loercher Pazicky 1986) (Quote by Diego Rivera) Foley, Barbara. Radical Presentations: Politics and Form in U.S. Proletarian Fiction, 1929-1941. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993; pg. 65.

Moore, Colin. Propaganda Prints : A history of art in the service of social and political change. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010. Accessed September 19, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central Pgs. 119-120

Plato.stanford.edu. 2007. Max Weber (Stanford Encyclopedia Of Philosophy). [online] Available at: <https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/weber/>

“prospectus for Dynamo” p. 2 (application to the American fund for public service, 25 March 1925, American Fund for Public Service Records, box 16, reel 11)

Realism, S., n.d. Social Realism Movement Overview. [online] The Art Story. Available at: https://www.theartstory.org/movement/social-realism [Accessed 12 October 2020].

Shapiro, Social Realism: Art as a Weapon (1973) Pg. 3, 15-16

“Social Realism Movement Overview and Analysis”. [Internet]. 2018. TheArtStory.org

Social Realism Movement, Artists And Major Works” 2018)

“The Passion, The Majesty, And The Politics Of Diego Rivera. | A Husk Of Meaning” 2011

Wolfe, Bertram D. “Diego Rivera–People’s Artist.” The Antioch Review 7, no. 1 (1947): 99-108. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4609195.